The Long-Awaited Promise

In the olden days, anyone flying into Washington Dulles International Airport had only a handful of ways to get into the city. You could hope someone loves you enough to pick you up, cram onto one of those shuttle buses or brace yourself to pay around $50 for an Uber or Lyft.

Then came the Silver Line extension. In November 2022, the Silver Line finally reached Dulles, adding six new stations and connecting the airport to the rest of the Metro system. After more than a decade of delays and billions of dollars over budget, the project was hailed as a major win for regional transit.

So this is good news, right? In short, yes—though not everyone’s thrilled.

A 2012 environmental analysis estimated the extension would generate about 17,900 daily trips by its seventh year and a Virginia study three years later bumped that up to 50,000 daily riders, the Washington Post reported. But those projections never held up. In the first year after the extension opened, more than three million people passed through the new stations, with Dulles accounting for roughly a third. On a typical weekday, about 5,000 riders enter through the airport stop—steady traffic, but nowhere close to the 50,000 once imagined.

This was supposed to be the moment WMATA re-entered its golden age: a megaproject built for booming offices, surging ridership and a region that was moved by Metro. But the promise of the Silver Line collided with a reality that changed before the trains ever arrived.

Before we get to the numbers, it’s worth remembering why this matters at all. WMATA is the country’s second busiest heavy-rail system, serving a region that 6.4 million people call home. What happens on a single line shapes how the entire region moves. For planners, it’s about recovery. For lawmakers, it’s about funding and long-term investment. And for riders, it’s about watching the system we depend on shift under our feet.

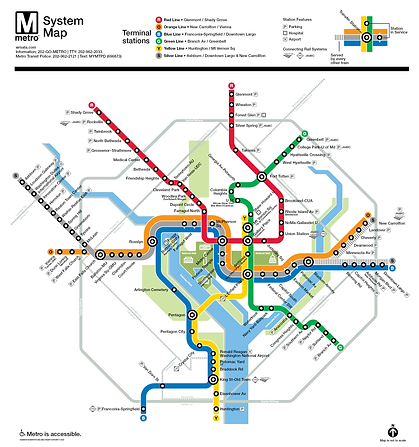

WMATA was created on February 20, 1967, through an interstate compact between DC, Maryland and Virginia to plan, build, finance and operate a unified regional transit system. Metrorail service began in 1976 with the opening of the first Red Line segment, and the system has since expanded to six lines, 98 stations and more than 130 miles of track.

The newest addition, the Silver Line, is the longest in the network and opened in 2014 in two phases. Its Phase 2 extension, stretching all the way to Ashburn, Virginia, finally connected Washington Dulles International Airport to the Metrorail system when it opened in late 2022.

To put the Silver Line in context, here’s how many stations each Metrorail line has served since the Red Line opened in 1976, based on WMATA’s official history timeline. Because service patterns have shifted many times, these numbers are approximate. (Also, check out this really cool video on the evolution of WMATA—I tried making a similar version and failed.)

A note on data: For the bulk of this project, I relied on WMATA’s Average Daily Rail Entries by Month summary, all compiled on 11/16/2025. This may skew the data a bit because:

-

WMATA tracks station entries, not unique riders. So if someone taps in at a multi-line station like Metro Center or L’Enfant Plaza, that one entry is counted once per line serving the station—even though it’s just a single rider.

-

I used WMATA’s average monthly data, which includes weekends. Most analyses rely on weekday ridership because it better reflects regular use, and weekend construction often drags numbers down. But I chose monthly data because what’s the point of a metro if you can’t use it on weekends?

-

I also didn’t include average daily non-tapped entries, aka fare evasion. WMATA does track this (don’t ask me how, though this might explain it), but it’s such a tiny share of overall entries that it’s fine to leave out.

-

"Present" in all charts refers to 11/16/2025, the date the data was collected.

Riders document their trip during the opening of the Silver Line extension at Dulles International Airport in November 2022. (Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

Riding Below Expectations

So how has the Silver Line actually performed since the 2022 extension? And did it arrive too late for the commuters it was meant to serve?

The second phase of the Silver Line extension finally opened after years of delays, political fights and ballooning costs, totaling about $6 billion for both phases. It was meant to be a major boost for the system: a new airport connection, new jobs, new development—all justified by projections of strong ridership. But by the time trains actually started running, the region didn’t commute the way it used to. Every line in the system fell off a cliff in early 2020, and none of them, Silver included, has climbed back to where they once were. WMATA’s recovery is sharp in its collapse and slow in its return.

And when you look at the data, that mismatch becomes obvious. The Red Line inches upward. The Blue and Orange Lines lag. The Yellow Line barely moved for months because its bridge was closed for an eight-month rehabilitation project from September 2022 to May 2023. And the Silver Line, despite the 2022 extension and all the hype around finally reaching Dulles, recovers, but not dramatically. The new stations get riders, but nowhere near the numbers planners imagined back when offices were full and average weekday ridership was around 600,000. The Silver Line’s pattern looks less like a breakthrough and more like a system adjusting in slow motion.

But now that the line has been fully open for more than three years (having launched on Nov. 15, 2022), several lingering questions remain. The Silver Line extension was designed for a pre-pandemic commuting boom that never returned. Did the expansion come too late, or is it simply still finding its footing in a region relearning how to move? And, ultimately, was it worth it?

Despite the hype and its exclusive link to Dulles International Airport, the six-station extension accounts for less than 10% of overall Silver Line ridership on average.

Looking deeper into the data reveals some striking commute patterns. Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport, served by the Yellow and Blue Lines and the only other airport in the region, sees far more activity than the Silver Line’s Dulles Airport station. And the data makes one thing clear: most people flying in and out of Dulles still aren’t taking the train.

All this investment, yet Silver Line ridership has barely budged. Since the Phase Two extension opened in late 2022, the line has consistently hovered around 20% of systemwide tapped entries—despite boasting the most stations and the longest track in the network.

Part of this may be due to how WMATA collects data and how I interpret it. The system can’t track which specific lines a rider actually uses, which benefits lines with more shared stations and inflates the importance of those stations. The six stations on the extension, being exclusive to the Silver Line, are therefore at a disadvantage.

On top of that, much of WMATA’s construction work happens on weekends and often affects the Orange, Blue, Yellow and Silver Lines, which pulls weekend ridership numbers into the overall averages and further complicates the picture. But an even bigger issue is more structural.

A possible reason is the system’s limited operating hours. Trains run from 5 a.m. to midnight Monday through Thursday, 5 a.m. to 2 a.m. on Fridays, 6 a.m. to 2 a.m. on Saturdays and 6 a.m. to midnight on Sundays. That leaves long overnight gaps when the system is closed, forcing airport travelers to rely on other options to get in and out of town.

Ribbon cutting at the Dulles International Airport Metro Station opening the new Silver Line extension. (Tyrone Turner / DCist/WAMU)

Airport ridership also runs up against a more practical barrier: parking rules. Long-term and overnight parking isn’t allowed at any of the Phase 2 stations except Wiehle–Reston East. So someone living in Ashburn can’t stash their car at their local station for a multiday work trip and take Metro to Dulles to save on airport parking. Metro and Loudoun County, which operates the Ashburn and Loudoun Gateway garages, prohibit it. It’s a small-sounding policy, but it has an outsized effect on how travelers decide to get to the airport.

And for some riders, the issues go beyond ridership numbers or parking policies. According to WMATA rider and Reddit user u/Ender_A_Wiggin, the problem is accessibility. They argue that the Dulles Metro station is difficult to find, and that trains should run faster on the long stretch between Spring Hill and Wiehle–Reston to make Metro more competitive with driving. In their view, driving still wins by a mile: Dulles continues to expand parking and improve highways, making the car the default option and Metro an afterthought.

(This summer, WMATA announced that the entire system would operate in Automatic Train Operation starting June 15 and that trains would return to their original top speed of 75 mph. Several outer portions of the Blue, Orange and Silver lines now run at 65 to 75 mph instead of 55, cutting about three minutes from end-to-end travel times on all three lines. I guess u/Ender_A_Wiggin was on to something after all.)

Tracks for Generations

Unsurprisingly, Dulles is the busiest of the six new stations, followed by the terminus at Ashburn. Overall, the extension accounts for 1.4 percent of systemwide Metrorail rides. In the first year, the six new stations averaged 794 riders per day, while the Dulles Airport station alone recorded 582,798 trips.

In early 2025, Phase 2 stations recorded a 16 percent uptick in weekday trips over the prior year, with suburban stops like Ashburn, Loudoun Gateway and Reston Town Center among the fastest-growing. Moreover, four of the six extension stations posted year-over-year ridership gains that outpaced the systemwide average, with Innovation Center leading the pack at 55 percent. Metro planners point to new density and station-area activity as the catalyst: where people live and work near the line, usage rises.

But zoom out, and the picture becomes clearer: most airport passengers, at either Dulles or National, aren’t commuting via Metro. This isn’t just a Dulles or Silver Line extension issue, but rather a systemwide one.

The Silver Line was built for a world of full offices and booming weekday ridership, but that world never came back. So where does that leave the Silver Line today—and what would it mean to rethink its purpose? If it didn’t deliver the ridership boom it was built for, what does success look like now?

Despite its hefty price tag, the extension is meant to deliver long-term gains. According to the U.S. Department of Transportation, investing in public transportation generates strong economic, social and environmental returns. Every dollar invested creates jobs, boosts business activity, encourages development and expands access to education, healthcare and employment—especially for underserved communities. Public transit also cuts gas consumption, improves energy efficiency, reduces air pollution and eases congestion by getting cars off the road.

Let’s be honest, no one wants to be stuck in Beltway traffic during rush hour anyway. And it’s not like the Silver Line is the only one facing challenges. Again, WMATA’s ridership-tracking methods can also make the line appear weaker compared with the rest of the system.

At the same time, there’s a wave of development along the Silver Line that’s only now coming into focus. Beyond connecting riders to the airport, one of the project’s biggest ambitions was to jump-start growth in the car-dependent stretches of Tysons, Reston and Herndon. And you can see that vision materializing: the Capital One complex rising beside McLean, The Boro reshaping the area around Greensboro and the ever-expanding mixed-use district taking shape around the Wiehle–Reston East Metro station. Much of that momentum took hold with Phase 1, while Phase 2 is still finding its footing.

So maybe success shouldn’t be measured by projections made for a different era, one when people still had to show up to work five, sometimes even six, days a week.

And maybe the Silver Line didn’t revive the old commute—but maybe it was never meant to. Its value lies not in returning WMATA to 2019, but in reshaping how the region moves for decades to come.

So the question shouldn’t be whether it was worth it, but how today’s data can help redefine what success looks like now: more flexible service, better weekend and airport options and a system built around current travel patterns. Because in the end, the Silver Line was never just a commute. It was a “generational investment.” And generational investments don’t answer to short-term expectations—they redefine what the next generation gets to expect.

Recently, WMATA won the Transit Agency of the Year award from the American Public Transportation Association, its first win in the category in nearly 30 years. (The APTA Awards honor North American transit organizations and leaders whose recent achievements have significantly advanced public transportation.) WMATA was also recently crowned the fastest-growing public transportation system in the country, growing by 15% over the last year. If anything proves why generational investments matter, it’s this: when you build for the future, eventually the future catches up.

In case you’re wondering how I compiled all this data, click here. And take it from someone whose first reporting stories were about station closures, train delays and even the Purple Line (now scheduled to open in late 2027). Lastly, if you want to learn more about WMATA, the Silver Line, transit planning and all that is interesting, check out this video (thanks, Jackson)!

Now step back, doors closing! 🚇